Are we reading Marx because he's awesome or because of the Bolshevik revolution?

Comments on Magness and Makovi (2022)

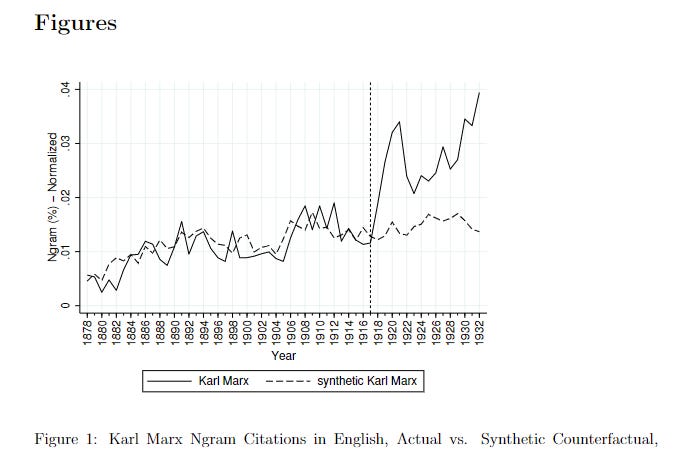

From Magness and Makovi (2022).

If you teach theory in a sociology department, you spend a bit of time reading Karl Marx. It’s no surprise. He’s one of the most cited writers of the last 100 years. When you teach Marx, you get some fairly straightforward books, like Communist Manifesto, which depicts a series of class struggles ending up in a socialist revolution. Then, you get to other texts which just vary in quality. Some are dense and hard to follow, while others are long and complicated applications of refuted ideas, like the labor theory of value. At the end of the day, you’d think that even socialist oriented readers would probably just pick the best parts of Marx and move on.

But that’s not what we have. Marxist social theory is one of the largest scholarly communities in the world. In the ASA, for example, there is a section on Marxist sociology, even though there is not a Weberian, Durkheimian, or Parsonsian sociology section. Heck, there is not even a DuBoisian section at ASA - and he’s probably the hippest classical sociologist in November 2022. The situation is truly odd - Marx preceded modern sociology (he worked from the 1840-1870s), he did not use distinctly sociological methods like surveys or ethnographies, and he did not call himself a sociologist.

Where does Marx’s oversize impact come from? Magness and Makovi (2022) in the The Journal of Political Economy offer a simple and straightforward answer: the Bolshevik Revolution. Their paper is essentially a quantitative affirmation of what many intellectual historians had noted throughout the 20th century. Marx had a real following among German socialists in the late 19th century, but he was catapulted to international fame in 1917.

This makes complete sense from multiple perspectives. First, and most obviously, power creates influence. We see it all around us - win an election and you can easily publish an op-ed in the local paper. Conquer the largest nation on earth and the whole world watches. Second, and this is specific to the Soviet case, we know that the Soviets invested a great deal in printing and distributing Marxist texts. For example, this was discussed in Vaughn Rasberry’s Race and the Totalitarian Century. The book is an exploration of why so many Black intellectuals veered into the Soviet orbit. Rasberry’s answer is simple - the Soviets invested a ton in cultural outreach.

So what evidence do Magness and Makovi have that it was specifically the Bolshevik revolution that boosted Marx to global stardom? They rely on citation analysis/bibliometrics. They identify a similar cohort of socialist intellectuals (“synthetic Marx”) and gathered data on how they often were cited. And before the 1917 revolution, Marx was cited in a way very similar to his group. Then, 1917 happens and he takes off like a rocket. See the picture at the top of this post. And of course, there are a number of robustness tests included in the paper.

If you are a committed Marxist or socialist, this paper shouldn’t change your view of Marx at all. He’s so awesome, he changed world history and this paper just proves the point. But if you aren’t in that camp, the paper should be a bit liberating. With an author like Marx, you’d typically extract a few tidbits and move on. But now that you realize that his fame is a bit of a historical fluke, you can now discuss him in this way, as Max Weber did in Economy and Society. For Weber, Marx was one socialist theorist among many arguing about the nature of a planned economy:

From Economy and Society, page 208 of the version translated by Keith Tribe 2019, Harvard University Press.

In the 800+ pages of Economy and Society, Weber only mentioned Marx directly one more time, on page 454, as discussing how the proletariat would maintain unity even if people were qualitatively different. If Weber could live without incorporating the entire intellectual apparatus of Marxism, you can too.

++++++

My books: Grad Skool Rulz - cheap advice manual for grad students / The history of Black Studies / Obama and the antiwar movement / A Social Theory book you will enjoy reading / Intro Sociology for $1 per chapter

"They identify a similar cohort of socialist intellectuals (“synthetic Marx”) and gathered data on how they often were cited. And before the 1917 revolution, Marx was cited in a way very similar to his group."

^^ Be careful: Even with their numbers, "Karl Marx"'s ngram in 1916 is way higher than other socialists; next-closest guy, Marx is 66% higher than. (So it's Abe Lincoln and Oscar Wilde scaling up "synthetic Marx.")

But if you look at their table 3, you'll see that except for Lassalle, they are using only last names of others. This shows Marx actually blows them out by orders of magnitude. Eg:

https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Marx%2CProudhon%2CLassalle%2CRodbertus&year_start=1840&year_end=1916&corpus=26&smoothing=3

Now to be sure, they have reasons. "Marx" is common last name etc. But I'm saying, if you think Marx was cited in same ballpark as those others circa 1916, no.